Scientists have been touting the potential of fusion energy since the 1920s, but until very recently commercial fusion had remained a distant dream. To better understand why, after decades of research, fusion is still not a part of the global energy mix, and why that is set to change, we spoke to Melanie Windridge, UK Director of the Fusion Industry Association, Communications Consultant for Tokamak Energy, and founder of Fusion Energy Insights.

Q: There’s an old joke that ‘nuclear fusion is the technology that is always 30 years away’ — is this true?

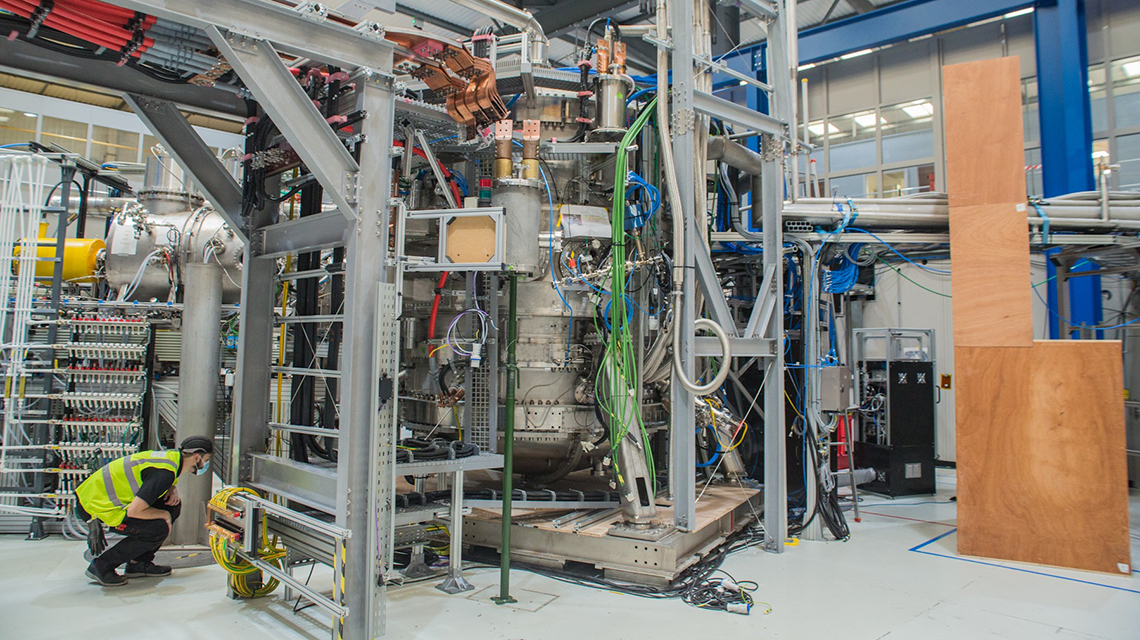

A: While that’s a classic fusion joke, it’s a bit sad because, in reality, progress is being made. Today, factors are coming together to accelerate advances in fusion. For one, the science has matured — we now have a good understanding of plasma physics, and concepts like tokamaks have achieved fusion reactions. On top of that, new technologies have come along like high-performance computing to improve plasma simulations and modelling; artificial intelligence and machine learning to optimize and control operations; and high-temperature superconductors that can produce much stronger magnetic fields to better confine fusion fuels. Today’s much more powerful and efficient lasers could boost inertial confinement fusion, and advances in manufacturing could help to bring down the costs of experiments and future power stations