The search for a new method

It was time to find a new pest control method, explains Vaughan Hattingh, a biologist and researcher, and now CEO of Citrus Research International (CRI), an industry-funded research outfit associated with the University of Stellenbosch. Some preliminary research on the irradiation of the false codling moth had been carried out in the 1960s, but there was no data available on whether it would work in practice. It was always going to be a gamble, he says.

Researchers at CRI and the country’s Agricultural Research Council were familiar with work by the IAEA, in cooperation with the Food and Agriculture Agency of the United Nations (FAO), in using SIT against the Mediterranean fruit fly. They began research in radiation biology and rearing techniques to see if the method could be adapted for the false codling moth. The Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, along with the United States Department of Agriculture, provided expertise and access to a network of specialists working on using SIT against other pests.

Thanks to funding from the IAEA’s Technical Cooperation Programme, Hattingh and his colleagues got a first-hand look at a rearing facility of a related codling moth in Canada. This helped them lay the groundwork to eventually rear and sterilize enough insects to test the technique on a 35-hectare plot in an isolated and particularly infestation-prone part of Slabber’s orchard.

“You did not want to drive through it because of all the fallen oranges on the ground,” Slabber recalls. “There were wasted oranges under each tree at any given time. It was a depressing sight.”

“The results of the test surpassed our expectations,” Hattingh says. “We realized that the false codling moth was a sedentary insect, so we could treat areas in isolation.” It is this characteristic that makes the moth a prime candidate for SIT: controlling the insect population in a defined geographical area, even down to a single orchard, keeps the area insect-free long term, because moth populations do not tend to fly far.

Public-private partnership for moth control

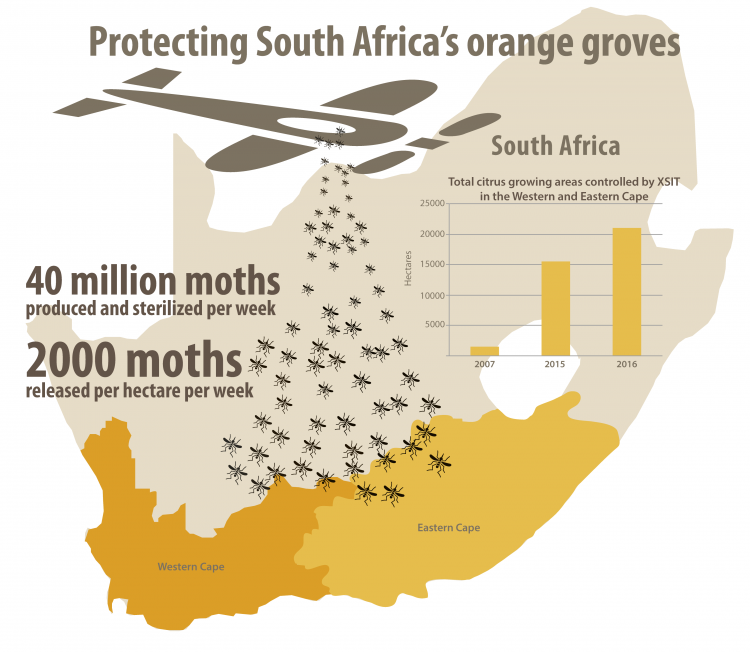

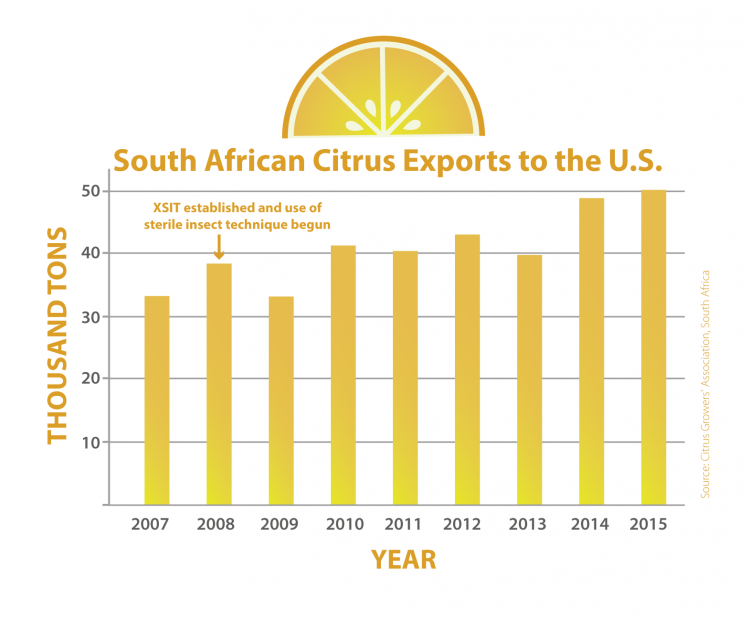

Following the success of the trial, the Citrus Growers’ Association and the government co-founded XSIT in order to industrialize the use of the technique. As of last March, the association fully owns XSIT, which charges farmers for its services and runs on a fully commercial basis. The area it serves has increased more than ten-fold since 2007, and it has contracts in place to further expand to a total of 21 000 hectares. At that point, its rearing facility on the edge of Citrusdal will be operating at full capacity, and any further expansion will require a new extension of the factory, or setting up operations in a new location, said General Manager Sampie Groenewald.

While the technique saved the area’s citrus industry, much work remains to be done. “First we thought SIT would be a silver bullet, but it wasn’t,” Groenewald said. In certain pockets of the valley it was not effective enough and moth populations would return.

Groenewald now advises his clients to use a mating disruption technique, along with SIT, particularly in moth hot spots. Under this technique, pheromones of the female moth are spread around the orchards in order to confuse males, which find females for mating based on their pheromones. Due to the presence of the artificial pheromones, they fly around without finding females to mate with and, after around five days, they lose their potential to mate and slowly die.

At XSIT, research is ongoing not only to further perfect the technique, but also to make it available in far flung areas of the country. The current method of producing sterile insects in Citrusdal and transporting them to other areas for release works well for neighbouring Eastern Cape, but it is not feasible for faraway places, such as Mpumalanga and the Northern Province. XSIT’s researchers, with support from the IAEA and FAO, are working on a technique that involves transporting the pupae, which would then be irradiated at another location in the north eastern part of the country. “We believe, the pupae would be less sensitive to transport,” Groenewald said.

XSIT has recently been contacted by growers of other fruits, which are increasingly infested by the false coddling moth.