Balancing how fertilizer, water and soil are used with agricultural crops has proven useful for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) that drive climate change and global warming. But striking an optimal balance requires understanding how these factors are influenced by different soil and environmental conditions as well as farm management practices. To help chart out ways to do that, scientists are using isotopic techniques to develop scientifically-based guidance that helps countries reduce and mitigate GHG emissions.

“In Brazil, we are already producing crops and meat using processes that help mitigate GHG while having a minimal environmental impact, but we need to better understand the impact of these processes on agriculture and reducing emissions. That’s how this project is helping us,” said Segundo Urquiaga, a researcher from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation who is participating in a project on mitigating GHG emissions supported by the IAEA, in partnership with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Brazil has been working with the IAEA for over 30 years to study the environmental impact of agriculture, which has generally accounted for over 35% of GHG emissions in the country. The country has successfully reduced GHG emissions by around 20%.

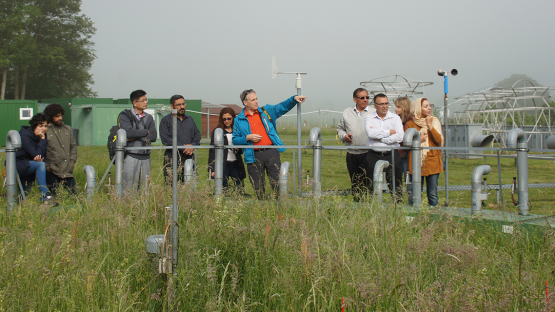

Brazil is one of 10 countries from around the world involved in this project, which began in 2014 and will run until 2019, where scientists are using isotopic and other techniques to study the natural processes of soil, plants and fertilizer under different climate conditions and to optimize agricultural practices to protect resources while reducing GHG. Some countries, like Brazil, are more advanced in their research, and are an important resource for those just starting out. But as each country faces unique environmental conditions and experiences, even more advanced countries can learn from.

“This project provides opportunities to share with different people and different countries. Some scientists are more advanced, and from them, we can expand our knowledge and develop a good network. But with so many different experiences, it helps all of us to speed up this research process that can take years,” said Nario Mouat Maria Adriana, a researcher from the Chilean Nuclear Energy Commission.

Reducing the GHG emissions (see The Science box) related to agriculture is one central aspect of combating climate change, but it has to be done in such a way that farmers can still earn a living growing the food we all need, explained Christopher Müller, an expert from Justus-Liebig University Giessen in Germany who is involved in organizing and implementing this project. “While it is clear that soil and plants have natural processes that can help us deal with the presence of GHG, there are so many factors that can influence how these processes work from one ecosystem to the next. If we can better understand how these factors work, we could help shape agricultural practices that improve our global situation while protecting our soil resources, which will become more critical in the future.”

Agriculture contributes over 20% of the global release of GHG emissions caused by human activity, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). GHG, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4), trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere by absorbing thermal radiation from the Earth, which in turn increases the Earth’s temperature. While the greenhouse effect is a natural process through which the Earth regulates its temperature and supports life, the excessive amount of GHG is leading to global warming.

Due to the impact of these gases on the world, the international community is working through agreements like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to achieve key goals to minimize the release of GHG and mitigate their impact.

As the scientific data is gathered, it can be incorporated into national approaches to GHG mitigation, explained Maria Adriana. “Policymakers need this information so they can make decisions on how they can mitigate these gases in a country, and also how to make incentive programmes to encourage farmers to adopt these methods. What we are doing now is part of that process,” she said.

Seeing the bigger picture

Through these global studies, the scientists expect to refine how they approach mitigation and get a better idea of how these processes work. “We need this kind of project because we can compare results to get a better understanding of the big picture,” said Segundo. “For example, only analysing carbon in one environment is not enough to understand how carbon works in another environment. We have to compare and learn from each other to help us shape our approach to get good results.”

Isotopic techniques are helping scientists uncover these details. These techniques involve isotopes, which are atoms of the same element that have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons. Nitrogen-15 is a stable isotope of nitrogen, while carbon-13 is an isotope of carbon. Both are found naturally in soil, fertilizer, water and plants. It is therefore possible to use these isotopes to measure and track how and when gases like CO2 and N2O are being formed, released and absorbed.

“Isotopic techniques are extremely precise and allow scientists to better understand what’s happening at each step of the process, which is something that conventional techniques cannot offer,” said Mohammad Zaman, a soil scientist at the Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture. “This kind of detail is important to unravel the complexities of these natural processes, which can differ significantly from one environment to the next. It helps identify how farmers can sustainably grow crops, save water, reduce the use of expensive fertilizers, all while protecting the Earth’s precious resources.”