After just 45 minutes, they have a diagnosis: PPR, peste des petites ruminants, a highly contagious virus that kills goats and sheep.

The farmer, Galgava Oumarou, is distraught: "I'm a poor farmer. I've no other source of revenue apart from these animals. Nearly all of them have died from disease," he says.

"I used to sell them to get money to take care of my family. Now that these goats are no more, I do not know what to do. Poverty has stepped in my house and I don't know how I will feed my family."

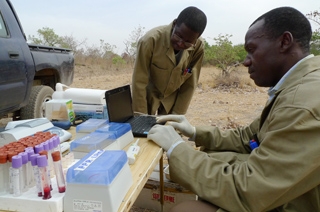

The technique the vets are using is known as "LAMP PCR"- Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification, based on real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction.

It sounds complex and it is. But scientists from the Joint Division of the IAEA and the UN´s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) have been able to condense four years of research using isotope technology and nuclear-related techniques into one small, portable kit.

The system is capable of performing rapid and highly accurate diagnostic tests, on-site, in under an hour. In the past, several days were needed to perform the same diagnosis in a well-equipped laboratory.

Senior LANAVET vet Dr Abel Wade says: "This technique has revolutionised traditional diagnostic procedures. In the past, I had to take samples, then return to my lab or wait for samples to arrive from the field. It could take weeks, even a month, before we actually got round to testing the samples and confirming an outbreak of a disease.

"Now, with this portable lab, we can run tests at the farms, in the bush. It's easy-to-use, quick and works in high temperatures. We can give immediate advice to the farmer to prevent further losses and to limit the spread of the disease."

Animal diseases are a major problem in many African countries, including Cameroon, where the majority of people depend on agriculture and livestock for food and income.

According to estimates from the African Union's Animal Resources Office (AU-IBAR), around 300 million people in Africa depend on livestock for their livelihoods.

But 25 per cent of these animals die annually from preventable diseases. In some cases, for example with poultry infected with Newcastle Disease, whole flocks are killed.

"I've seen people crying because of outbreaks of diseases like foot and mouth disease, which can kill more than 100 cows - that's 50 percent of one herd," says Dr Wade. "Cattle are especially important here because you can use cows for their milk, meat and for farming. If you need some money for hospital fees or a scholarship, then you sell cows at the market."

The project, which led to the development of the portable diagnostic platform, was originally launched in 2008 as a direct response to the needs of many countries to diagnose Avian Influenza rapidly, in rural settings and outside of a conventional laboratory.

FAO/IAEA animal disease expert Dr Hermann Unger says: "The rapid diagnosis and confirmation of an infectious disease, best at an early stage, is the prerequisite for its cost-effective control and to curb its spread."

"As most of the diagnostic techniques used so far needed laboratory-based equipment, the development of the LAMP technique in a portable, robust and simple kit format, which makes it possible to confirm disease in the field in less than an hour, is a major step forward."

With an early diagnosis, quick decisions can be made on how best to contain and control a disease - by quarantine, treatment or vaccination. Fast action can not only limit damage to the affected herds, but can also prevent the disease from spreading into neighbouring villages or even other countries.

The LAMP PCR device can run tests simultaneously for up to eight diseases, including foot and mouth disease, African swine fever and peste des petites ruminants, as well as for diseases such as avian influenza (H5N1), Rift Valley fever and bovine tuberculosis that affect both animals and humans.

"Of course, Africa is not the only place where we're contributing with this new technology," says Dr Unger. The IAEA, through its Technical Cooperation Department, has already provided devices costing around 4,000 euros each to more than 30 countries in Africa and Asia.

"In Sri Lanka, for example, we're seeing good progress in applying the technology on leptospirosis, an animal disease that is also infecting rice farmers," Dr Unger says.

Livestock supports the livelihoods and food security of almost a billion people worldwide. As populations increase, countries not only need to increase livestock production, but also need more efficient tools for the prevention, diagnosis and control of animal diseases.

Nuclear and nuclear-related technologies have an essential role to play in maintaining animal health and protecting vulnerable communities.