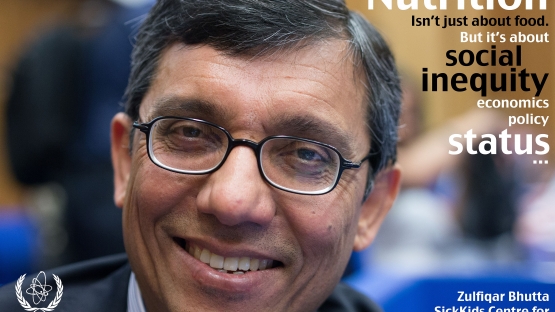

While attending the IAEA International Symposium on Understanding Moderate Malnutrition in Children for Effective Interventions from 26 to 29 May 2014, Zulfiqar Bhutta, Professor and Founding Director, Centre of Excellence in Women Child Health Aga Khan University and Robert Harding Chair in Global Child Health and Policy, and Co-Director, SickKids Centre for Global Child Health, spoke to the IAEA's Sasha Henriques about the ways social inequality affects nutrition:

"Nutrition isn't just about what you eat.

"It's about education, poverty, ethnicity, marginalized populations, community empowerment, social status, access to resources and access to medical care. These are things that are probably more important in terms of nutritional outcomes than just giving people pills to swallow or food to eat."

Why is everything outside the health sector important?

"If women and girls had access to opportunity, education and employment, they would be able to determine a better track for their own health and nutrition outcomes in a way that pure interventions and nutrition interventions cannot. For example, if you are receiving an education, you're more likely to be able to make decisions for yourself - such as staying in school, rather than getting pregnant or married.

"As academics we are working to generate evidence to support the use of strategies that take the social determinants of nutrition into account. But most importantly, my own group works on solutions, and ways for countries to scale up these solutions, that is, to take a small solution and make it available to an entire nation in a systematic, effective way.

"Early and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months for example, is one of the best interventions in terms of gains for child and maternal health that has been scaled up, using promotion, peer counselling and other means of implementation, and is therefore making inroads in many countries worldwide.

"Yet, a decade ago exclusive breastfeeding was not available in many countries beyond 20% or 30% of a population. Today those rates have gone up because of the concerted efforts of the nutrition community, and government buy-in. That's just one example of a nutritional and behavioural intervention that can make a difference."

Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months doesn't seem to have anything to do with the social aspect of nutrition...

"But it does! If you're poor, and you don't have access to services like health care providers and community health workers, where are the opportunities to exclusively breastfeed your baby for 6 months?

"Unless you have social protection in terms of rights to employment and adequate paid maternity leave, your likelihood of quitting breastfeeding to do other things is that much greater.

"So it's a complete misnomer to imagine that exclusive breastfeeding is universal amongst poor people; it is not. Because poor people have to work! Even beyond situations of abject poverty where countries have maternity leave for those in the normal workforce, it's usually something like 3 months. So how are women expected to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months?

"Therefore a lot of these things pertaining to nutrition and health have to do with social structures, policies, and their implementation."