A nuclear technique and its resulting collective data have dispelled longstanding beliefs about metabolism – the chemical processes the body uses to produce energy. According to a study published in the journal Science earlier this month, prominent stages of life, like puberty, pregnancy and menopause, as well as gender and mid-life aging, do not affect metabolism as much as many believe.

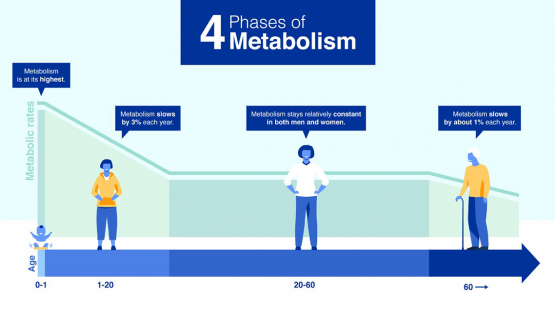

The results of the study showed that metabolism can be divided into four life phases:

- Up to 1 year of age: Metabolism is highest, about 50 per cent higher than for adults.

- 1 – 20 years of age: Metabolism slows by 3 per cent each year.

- 20 – 60 years of age: Metabolism stays stable.

- After 60 years of age: Metabolism slows by about 1 per cent each year.

“Many of our beliefs surrounding metabolism were based on studies with limited data, and assumptions were made based on the little information we had,” said Alexia Alford, Nutrition Specialist at the IAEA’s Division of Human Health. “This is a landmark study for the IAEA and demonstrates how the application of isotopic and nuclear techniques are vital to understanding human health.”

The study illustrates how metabolism changes from birth to the ninth decade of life. "We know now, for example, that metabolism doesn’t slow in middle age, and women and men do not have different metabolisms,” Alford said. “The study also highlights the importance of the first year of life for development, when the high energy expenditure is due to the increased energy demand of growth and development.”

The data for the study was derived using a stable isotope technique, known as the doubly labelled water (DLW) method (see THE SCIENCE), and was gathered from the IAEA’s DLW Database, launched in 2018, which provided experts with the data of 6 421 people from 29 countries, aged eight days to 95 years. The technique is non-disruptive – individuals taking part in studies can go about their daily lives during the measurement period.

Experts evaluated the effects of age, body composition (the proportion of fat and fat-free mass) and gender on total energy expenditure or the number of calories burned. “The findings will help scientists better understand important questions about metabolic health and how to help people live healthier lives at every life stage,” Alford said.