Cotonou, Benin – With increased shipping activity along its coast and mining in the region, Beninese authorities are concerned about pollution that could affect the environment and impact the country’s agricultural products. They have turned to the IAEA for assistance in monitoring radioactivity levels, heavy metals and other pollutants in the ocean and on the coast, and to help local experts estimate the amount of contaminants in the food supply based on people’s diets. With the infrastructure for environmental monitoring and diet studies now established, results are expected to be available before the end of the year – a major step towards improving food safety.

“Until recently we were in the dark as to how much environmental contamination there is and whether people take in harmful substances above recommended limits,” said Kinnou Kisito Chabi Sika, General Manager of the Central Laboratory of Food Safety Control (LCSSA). “Soon we will understand a lot more.”

Environmental protection and food safety go hand in hand, which is why the IAEA advocates such a coordinated approach in countries it works with, said Miguel Roncero Martin, who is in charge of the IAEA’s technical cooperation projects in Benin. “If you have a really contaminated environment, how could you produce food that is safe to eat?”

Environmental monitoring stations

Preliminary results from 15 monitoring stations around the country set up this year suggest that both heavy metal and radionuclide levels are below safety limits, said Etiennette Dassi Gnaho, Head of the Environment Surveillance Laboratory established with the help of the IAEA in 2014. The lab’s alpha and gamma spectrophotometers, used to evaluate radiation levels and to verify heavy metal concentrations, were cofinanced by the IAEA and the Government of Benin. All of the lab’s five professional staff received training at similar institutions in Morocco and Madagascar, with the support of the IAEA technical cooperation programme.

Heavy metals such as lead, mercury and cadmium as well as copper, phosphate and radioactive substances that could be released into the environment as a result of phosphate mining are of particular concern, she said. Verifying water quality in the vicinity of where treated sewage enters the ocean is also a priority for the government.

As of earlier this year, samples are taken from ocean water, coastal sediments and fresh water. The addition of soil samples from inland will follow next year, she added, along with the implementation of a strict surveillance plan developed with the help of the IAEA and experts from Morocco.

Total diet studies

The presence of pollutants like heavy metals is particularly worrisome if they end up in food. Heavy metals are not eliminated from people’s bodies, but accumulate over an individual’s life, and if their intake is too high, they could reach dangerous levels, affecting the nervous system.

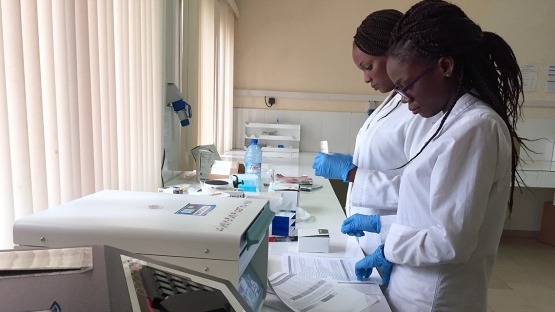

In order to ensure that the amount of heavy metals taken in with food does not reach dangerous levels, researchers first need to model the diet of the population, so that, based on people’s consumption, acceptable concentration limits in the food and the environment can be established. These levels can be established through what are known as total diet studies – models that take into consideration the amount of food people eat over their lifetime. Such studies – which use nuclear derived analytical techniques – will for the first time be carried out later this year following the receipt of equipment, training and advice from the IAEA in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Through the technical cooperation programme, seven chemists and microbiologists working at the food safety lab received training in Belgium, Botswana, the Czech Republic, Morocco, Sudan and Zambia, Chabi Sika said.