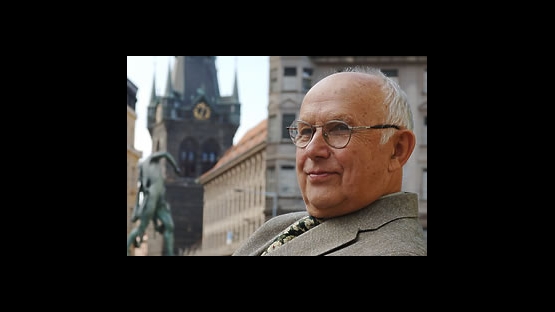

There is little that Professor Vladislav Klener does not know about the health effects of radiation. It´s been the Czech doctor´s life work for four decades. It is this knowledge and that of his contemporaries that his country is urgently trying to record and preserve.

Like the snowy-haired professor, 35% percent of the Czech nuclear workforce is due to retire in the next five years. How to transfer their wealth of knowledge to tomorrow´s nuclear workforce is a tough challenge in an age where the industry is stigmatised as dangerous and still often frowned on at cocktail parties. The jobs are there, but the needed influx of clever young blood just has not been enrolling.

It is a far cry from the Czech Republic´s former communist days when a young Prof. Klener saw brighter opportunities in the nuclear arena and the promise of an energy source "too cheap to meter" reigned. He made the switch from being a doctor of internal medicine, to a career as a medical and radiation protection specialist.

"The nuclear boom is over," Prof. Klener says. "Now we are facing a gap and we didn´t educate our successors." It is a similar scenario faced by much of the world. The average age of the global nuclear workforce is around 50 years. In 15 years, half of the workforce will retire.

For the Czech Republic's chief nuclear regulator, Dr. Dana Drabova, the situation is setting off alarm bells.

"In five to ten years we will have a gap in employees who hold knowledge critical to nuclear power plant operations and radiation safety," Dr. Drabova says. "If the knowledge is only in the heads of people it is difficult to reconstruct. To keep the knowledge living you need an overlap of generations."

How to assist countries like the Czech Republic survive the "information gap" is a focus of IAEA efforts internationally. Strategies range from recording the data and developing IT systems to store it, to providing hands-on help to countries. At the Krsko nuclear plant in Slovenia, the IAEA, jointly with the World Nuclear Organization (WANO), worked with the plant´s management to systematically capture undocumented information on safety and technical insights from retiring workers.

It is this tacit knowledge of experts - who know more than they might say or write down - that that is often most difficult to capture, says IAEA specialist Andrei Kossilov in the Department of Nuclear Energy.

It was a dilemma piano manufacturer Steinway faced when it decided to resume production of a model it had discontinued some time ago. The world-renowned company had lost the corporate memory and blueprints about how to produce the piano again. The piano scenario is not one the world can afford to face when it comes to the safe running of a nuclear power plant.

In the Czech Republic, nuclear plants and knowledge management are twin pillars. "Every third light bulb in Czech is powered by nuclear," notes Dr. Drabova. "If you want to keep the lights on ten years from now, then you need to keep the knowledge."

The challenge, says Mr. Kossilov, is to create an environment where tacit knowledge is routinely shared and disseminated, through multiple means. "No information management system can replace the need for face-to-face interactions," he says.

Training and well-equipped research centres are vital to bigger picture efforts to attract and retain the best and brightest students and ensure an overlap. Last year the IAEA supported over 2 000 participants in training courses and some 1 500 fellows and scientists through its technical cooperation programme.

Czech PhD student Daniel Seifert uses a cyclotron procured by the IAEA to learn his tools of the trade. He is on the way to becoming a radiopharamcist, which is a branch of nuclear medicine used to understand human disease and develop effective treatments. He dreams of research and discovery. "Everyone wants to be a millionaire," Daniel says with a smile. "But the chance to work in nuclear medicine offers a real chance to help people. That's why I do what I do."

Daniel is part of the changing nuclear guard. The IAEA is working with countries to ensure that students like him have the knowledge they need to keep the benefits of nuclear science alive.